ARTEK Recordings

Reviews of CD 3

Click to Order Recording

ARTEK Recordings |

|

1. American Record Guide

Brahms: Violin Concerto,

Saint-Saens:

Concerto 3

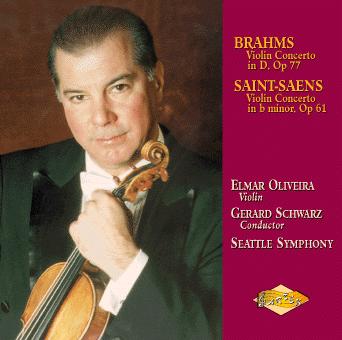

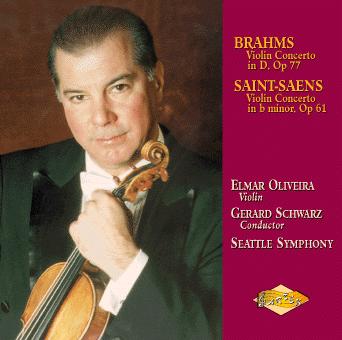

Elmar Oliveira; Seattle Symphony/Gerard Schwarz—Artek 3 (Allegro) 69 minutes

The highest level of fame has always eluded Elmar Oliveira—strange when you reflect that he is the only American ever to win the gold medal at the Tchaikovsky Competition. (Remember all the hoopla when Eugene Fodor won the silver?) On this disc Oliveira plays two of the major concertos in the repertoire, so this is a good opportunity to assess his talents.

I was struck by how familiar the Brahms sounded, especially in I. I felt that Oliveira and I had the same record in our collections, namely the classic David Oistrakh with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra from the late 60s. There is a nearly comparable breadth and intensity in the orchestra’s accompaniment, and Oliveira phrases very much like Oistrakh, even matching the tone color Oistrakh used in each phrase. Although Oistrakh’s influence is clearly present (can anyone who has heard that recording possibly forget it?), it wouldn’t be fair to say this is merely a copycat performance. It is clear that Oliveira’s heart is in this music, and there are many moments when I felt like holding my breath to listen as closely as possible. Maybe someday EMI will finally reissue that classic performance on CD, but in the meantime those whose old LPs are wearing thin may listen to this disc with pleasure. On CD I still prefer Perlman/Giulini and Kremer/Bernstein.

The Saint-Saens doesn’t bring any other performance to mind, but it too is heartfelt and moving. I’m still under the spell of the peerless concert recording from the early 60s by Michel Schwalbe (Jan/Feb), but Oliveira’s involvement makes this disc worthwhile. MAGIL

2. The Strad

Strad Selection *Concerto disc

Brahms Violin ConcertoSaint-Saens Violin Concerto no. 3 Elmar Oliveira (violin); Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz (conductor) Artek AR-0003-2

Aitken Aspen Concerto:Rameau Remembered; In Praise of Ockeghem; Elmar Oliveira (violin); Scott Goff (flute); Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz (conductor) Artek AR-0004-2

A true aristocrat of the violin, Elmar Oliveira plays with a relatively small-scale, jeweled tone that recalls the like of Christian Ferras and Wolfgang Schneiderhan. Yet his impassioned artistry imbues even the most familiar of phrases with a warmth and thrilling inevitability that recalls Isaac Stern in his heyday. Purity is the watchword here, with even the most indomitable passages in the Brahms Concerto emerging with a litheness and tonal transparency to set the ears tingling. Like Nathan Milstein he sustains amplitude by the subtlest use of extended bow strokes rather than merely applying more pressure; as a result there are remarkably few ‘noises off’ even when he is going flat out. This is the kind of playing that inspires concentrated listening simply because of its fascination as pure sound, even if some may prefer a more overt emotional response to Brahms’s physically imposing writing.

Oliveira comes out with all guns blazing for the opening of the Saint-Saens. I cannot recall having heard this fabulous work’s many exquisite turns of phrase voiced so ravishingly (nor so immaculately tuned) since Henryk Szeryng’s 1969 recording for Philips. The finale’s pyrotechnics are thrown off with nonchalant panache, although once again it’s the lyrical moments that linger longest in the memory. The recording is well balanced (perhaps a shade bass-light), with the soloist begullingly caught by the microphones.

Oliveira is as renowned for his championing of contemporary scores as for his mastery of the classics. No surprise, then, to find him tackling a concerto just ten years old and originally written for Joseph Swenson. Hugh Aitken recently retired from William Paterson Unicersity in New Jersey following 20 years at the Julliard School. The three-movement Aspen Concerto’s brand of ‘fourthsy’ neo-Classicism is redolent of Hendmith with a smattering of Bartok thrown in for good measure. It is skillfully crafted music, which Oliveira plays with great beauty of tone and moving intensity. Rameau Remembered is, as its title suggests, an imaginative rethink of French Baroque territory in which fragments dislocated from a bygone age are redressed in contemporary garb. In Praise of Ockeghem for string orchestra takes the terms of reference back still further, although this is less a pastiche than a moving homage. Crystal-clear recording; gripping performances. Julian Haylock

3. Fanfare

Brahms: Violin Concerto, Saint-Saens: Concerto 3

Elmar Oliveira (vn); Seattle Symphony/Gerard Schwarz, cond—Artek 3 (Allegro) 69 minutes

When then-staffer Michael Fine interviewed Elmar Oliveira way back in Fanfare 11:5 he bravely raised a sensitive but unavoidable question: Why had Oliveira made so few standard-repertoire recordings, particularly of great concertos? Fast-forward a decade, and although Oliveira has now made some important recordings, and is among the most technically assured violinists around, only now do we have two bedrock 19th-century concertos from this artist. The results are what one would hope for and expect. While in some of his concert broadcasts Oliveira can sound as if he is coasting a bit, here we have playing that reflects not only this artist’s customary polish and tonal warmth, but also the characteristic interpretive toughness and intensity that I have heard in his recitals and concerts with the orchestra here in Milwaukee over the years.

Albert Spalding wrote in his autobiography that turn-of-the-century concert violinists accepted the Saint-Saens in the standard repertoire and debated whether the Brahms would ever join it. Both pieces are by pianists, and take work to keep “in the fingers,” both are fundamentally serious and ambitious works that make demands on conductor and orchestra as well as soloist, and both composers exploit the coloristic possibilities of combining solo violin with winds: Saint-Saens merges, at the close of his second movement, high violin harmonics in octave with low solo clarinet in what remains an absolutely distinctive sonority, while Brahms not only created an oboe part that remains a test for a true artist (nicely played on this recording), but, particularly as brought forth by Schwarz, Brahms used his horns as musical punctuation, echoing the very pronounced bowing articulation expected of the soloist.

Oliveira plays both works in virtuoso manner. His big interpretive gestures tend to elevate Saint-Saens in stature as they downplay an Olympian side to the Brahms in favor of something earthier than we hear from, say, Menuhin, Oistrakh, Perlman or Milstein.

The Brahms Concerto is hardly trivialized by this approach. The fire and passion of the soloist’s entrance is a hint that Brahms was mindful of the piece’s virtuoso potential, and Oliveira plays up that element. What keep this interpretation from joining the highest levels is that Oliveira can be casual as to rhythm in passages where some strictness is key to Brahms’s metrical game with the listener. In the third movement I sense the soloist trying to push Schwarz into picking up the tempo a bit. The Saint-Saens’s opening solo is also vehement (sonically the violin sounds more front-and-center than in the Brahms), and in an interpretive continuum with Milstein and Grumiaux the last word in suavity. Lin and Francescatti bringing a more vivacious virtuosity to the music, and Kaufman going to the other extreme of crushing intensity, Oliveira is somewhere between the Francescatti and Kaufman approaches. He pours on the big tone very thickly in the slow movement, maybe too thickly to capture the essential, crystalline purity so compelling in the Milstein and Grumiaux recordings. As usual the final octaves of violin harmonics and clarinet defy sounding as they do in a real hall. The third movement receives a rather tempestuous account, full of drama (with the coda sounding, as usual, just a bit tacked on by the composer). Except for some raggedness in the string section, the support is up to major-league standards. Overall, not “the best” in either concerto but a fine recorded representation of the prime of one of the more important solo violinists before the public today, and thus most welcome to this artist’s admirers. David K. Nelson