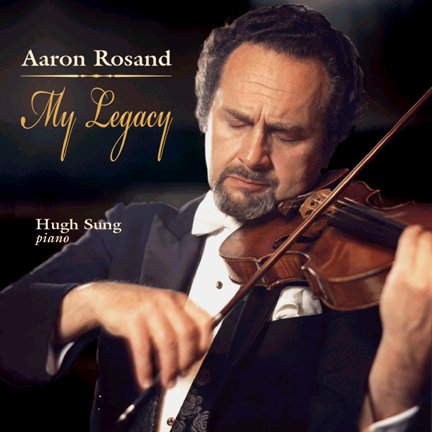

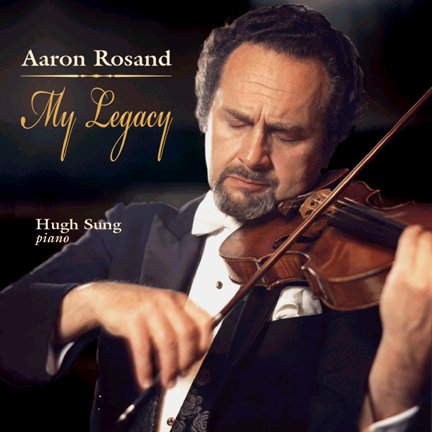

ARTEK Recordings

Reviews of CD 11

Click to Order Recording

ARTEK Recordings |

|

1. American Record Guide

Szymanowski: Nocturne & Tarantella; 3 Myths; Romance; Song of

Roxanne,

Chopin:

4 Nocturnes,

Aaron Rosand, violin. Hugh Sung, Piano.Artek 11 -- 73 Minutes

This is a beautifully played, well-conceived recital of Polish music that Rosand dedicates to his father, who was born in Lowicz, Poland at the turn of the last century. His father started him on the vioin and sacrificed during the Great Depression to pay for violin lessons for his son.

Rosand plays each piece as to the manner born. The Szymanowski miniatures are fevered and ethereal, the Chopin Nocturnes ardent, and the Wieniawski bonbons playful. Rosand still has the technique to pull off this program, but he doesn't aim for flash anymore, preferring to play each work as a character study rather than as an opportunity for showing off. An interesting note for violin aficionados: Rosand plays the same Guarnerius del Gesu violin that was played by Paul Kochanski, the violinist who worked with Szymanowski to arrange and compose his music for violin.

2. Classical Music on the Web

Rosand's Legacy, as one can determine from the programme essays, is Polish. To this a little greater spice is added becaus he plays the ex-Kochanski Guarneri; Szymanowski's Three Myths were dedicated to that magnificent but sadly short-lived violinist. Recorded in May 2001 Rosand shows few signs of technical decline and none at all of a loss of expressive nuance. Part of something of a Golden Age of American violinists -- in an era in which Isaac Stern rules the roost domestically -- Rosand has recorded for a number of smaller labels and the latest is Artek. He is a marvellous musicial and as he showed during his last London visit, when I heard him at the Wigmore Hall, his ability to coax a sweet yet powerful tone is unimpeded, his slides still apposite and tastefully deployed, his whole artistic persona one of generous engagement -- one of the very best violinists of his generation.

He catches the soaringly fractured line in Szymanowski's Nocturne, its folk impulses perfectly understood and in the Tarantella he is effortlessly virtousic, a suitably dramatic orator; my only compaint is that the balance favours the excellent pianist Hugh Sung, a splendidly active musician but here one who can submerge the violin. The phantasmagoric intensity of the Fountain of Arethusa is treated to Rosand's special poetic intensity and luscious deployment of expressive devices. His intonation remains under control, his playing one of optimim poeticism. In Narcissus he seems to inhabit its rapturous introversion -- intoxicating -- and he flutters and skitters, running through daredevil heroics in Dryads and Pan. But he is just as capable of catching the essence, the core of the hallucinatory, otherworldly syntax even down to the puckish, throwaway spectral finish. Rosand lavishes the full range of his bewitching tone colours on the Op. 23 Romance -- very tender playing with superior and sophisticated finger position changes.

He also plays a group of Chopin Nocturnes; two in nowadays somewhat overlooked arrangements by August Wilhelmj, one by Sarasate and one by Milstein (the familiar C sharp minor). I like the way he points up the rather idiomatically solemn religiosity of the central section of the E minor ( in the Wilhelmj transcription). Perhaps he lacks Milstein's stillness in the C sharp minor but this is still a good performance. In the Wieniawski group his Capriccio-Valse is not too fingerbustingly motoric -- it has colour, it has luscious tone, it has poise. The moto perpetuo type Saltarelle (actually a Caprice) is in true nineteenth century showstopper tradition -- and Rosand doesn't let us down -- and the recital ends with the more familiar Souvenir de Moscou. Here is more evidence of the sheer elegance and precision of his playing. The harmonics are negotiated with panache though the tempo is never excessive.

My admiration for Rosand has lasted a long time and is undimmed. His latest release continues in the tradition of his august discographic predecessors. He is a violinist we will hear whatever he plays.

Jonathan Woolf

3. Fanfare

Artek designated Aaron Rosand's program of music by three Polish composers "My Legacy," referring generally to his father's birth in Lowicz, Poland, but specifically indicating intimate connections with individual pieces and composers as well. Szymanowski wrote for violinist Paul Kochanski, an earlier owner of Rosand's 1741 Guarneri (of which the The Strad has made a poster available); Chopin's Nocturne in C# minor was Rosand's mother's favorite piece; and, throughout his long career, he's championed works by violinist-composers like Wieniawski.

Rosand recorded Artek's collection in May, 2001, pushing, even then, towards the middle of the seventh decade of his career. Rosand elevates Szymanowski's Romance from vignette to ecstatic declamation. Violinists used to play Chopin's works on the violin (Milstein once noted that he had strengthened his technical mastery by playing directly from Chopin's piano parts); and Sarasate, Wilhelmj, and Milstein made arrangements that reveal almost as much about their violinistic predilections as about Chopin's pianistic ones. Wieniawski, who anticipated the modern continuous vibrato and championed Paganini's flying staccato, may have inspired the generation of violinists who followed him, but he became for a time the bane of program builders who'd been bitten by the sonata bug (I remember the scorn with which some of my classmates regarded him in the mid 60's). Rosand's sympathy for this repertoire has matured over the years. For example, he doesn't feel compelled to push the Fourth of Wieniawski's Etudes-Caprices, op. 18 as many violinists do (it's marked Temp di saltarella, ma non troppo vivo), although it's clear tha he could if he wanted to; on the contrary, he allows the bow to spring naturally from the string, revealing the study's charm rather than simply making it a brief pyrotechnic rocket. Wieniawski'sEtudes (op. 10, too) provide an introduction to stylistic as well as to technical aspects of violin-playing.

Rosand, like Milstein, who admired him, seems capable of spinning these magical tonal webs forever. In fact, while his upper registers remain brilliant and his G string commanding, his middle range has, if anything, grown richer and warmer, more insinuating and more subtle. Hear him while you still can. And this thoroughly violinistic repertoire's his meat, so by all means hear him in this.

Robert Maxham